Red Power, a concept that emerged in the 1960s, describes the rise of a shared awareness among the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island of their unique rights and identities.1 Red Power was a wave of momentum that pushed existing struggles of Indigenous resistance to the forefront. This momentum was created during an era of anti-war protests. Widespread social change was ushered in by young people gathering, especially on college campuses, to protest government war-making in Vietnam.2 Red Power was also inspired by Black Power, a similar concept used to describe movements for Black liberation that arose primarily in the United States as well as the Pacific Islands.3

During the Red Power era of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Indigenous activists used strategies like occupying buildings, organizing mass cross-country protests, and hosting community gatherings to discuss current events. These strategies combined traditional Indigenous leadership with new ways of organizing that were inspired by the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. Red Power helped affirm the agency of Indigenous peoples, where Indigenous peoples have full control over their own lives and nations without external influence. This is important because governments have long tried to control Indigenous peoples by, for example, making it illegal for Indigenous peoples to practice their cultures, speak their languages, and raise their children. However, we must note that Red Power is not just something of the past. The values and mobilizing efforts of Red Power have been passed down through generations of activism and are still alive and well today. Indeed, we stand witness as Indigenous activists from around the world continue pushing back against settler-colonial systems and structures.4

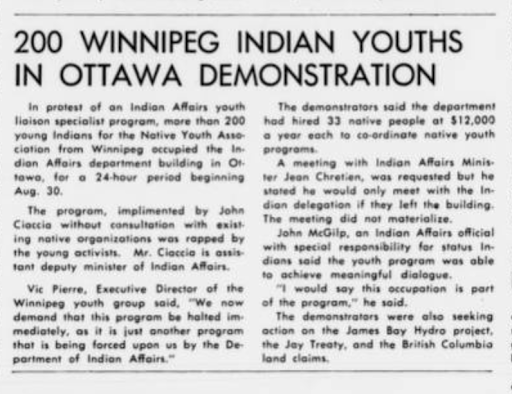

Red Power is usually associated with the United States because many movements there were very influential and gained international attention. However, the spirit of Red Power could not be contained in just one country. For example, in 1973, Arthur Manuel (Secwépemc) organized a twenty-four hour occupation of the Department of Indian affairs (now called Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada).5 Over three-hundred and fifty Indigenous youth from various nations participated in the occupation.

This lesser-known example shows that many Indigenous peoples in Canada were active participants in Red Power mobilizations. While the occupation of Indian Affairs is a powerful moment of Red Power activism in Canada, it is just one example among many.

As we explore the exciting world of Red Power and reflect on how the movement may have shaped the world today, we must consider that people have different opinions about the role that Red Power played in organizing Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island. As with all labels, we should be careful when describing certain groups and events as being a part of the Red Power movement. Often, more context is needed to best understand how Indigenous activism has looked at different historical periods. What we may mean when we talk about Red Power is diverse, and there’s a wide array of different strategies and futures to which people are working towards.

1. Turtle Island is a term used by Indigenous peoples to refer to North and Central America.

2. For more on youth activism during the Vietnam War era, visit an interactive website created by the University of Washington’s Antiwar and Radical History Project.

3. The movement was founded in 1966 by Bobby Seale and Huey Newton, who met at Merritt College in Oakland, California. However the movement had a global reach including offshoots created in Australia (the Black Panther Party) and Bermuda (The Black Beret Cadre).

4. These systems use violence to divide Indigenous nations, limit Indigenous autonomy, and take over Indigenous lands and resources.

5. Arthur Manuel was a prolific political leader for the Secwépemc Nation. His father, George Manuel, served as president of the National Indian Brotherhood and the World Council of Indigenous Peoples.